“How di bodi?” has to be our favourite greeting of all time.

While cruising around the towns and villages of Sierra Leone - or “Salone” as the locals call it - we were asked this countless times. We would use one of the following common responses:

“Bodi fine!”

“Noh bad!”

“Tank God.”

Telling strangers that we had “fine bodies” brought smiles to our faces - and so theirs - every time.

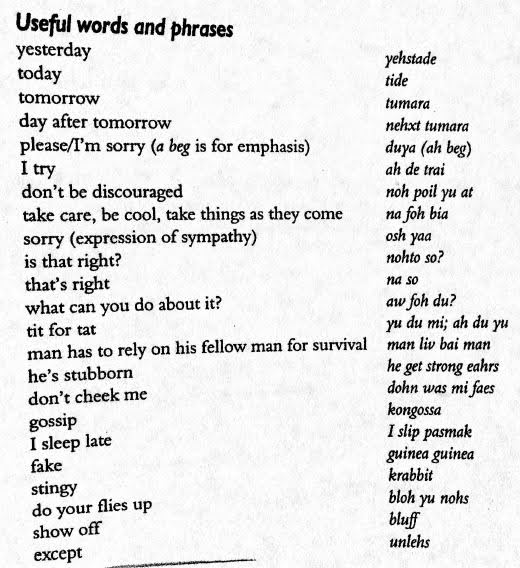

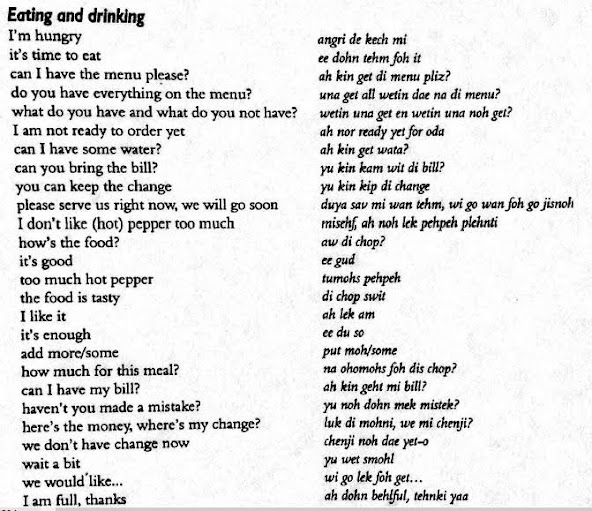

With our newly acquired smattering of Liberian pidgin, it was not too hard to pick up the Sierra Leonean pidgin - called Krio (“Creole”) - despite it having some idiosyncrasies due to the country’s partial Jamaican heritage. The strangest thing with learning pidgin is that you have to learn which words and syllables to leave out and there are a few totally new words to learn. The most confusing part of the language for us was that some people use the word “nah” (now) to emphasise the present tense (“I nah go”) which sounds very similar to “noh” which indicates the negative (“I noh go”) so we were often confused as to whether things were happening “now” or not at all. Here is a screen shot from an old guide book on some funny/strange and supposedly useful phrases for travellers (tip: pronounce the Krio phonetically and you’ll hear the link with English).

We had expected, given the similarity in their histories, that Sierra Leone and Liberia would have a lot more than a language in common. And yet, as soon as we arrived at the border we could tell that we were in for a surprise. The Sierra Leoneans have a remarkably sophisticated Health Screening building where your temperature is scanned and your identity recorded through the scanning of your eye’s iris. The immigration procedure was the usual low tech affair with a sense of arbitrariness about the rules, but after a relatively painless procedure we found ourselves climbing into a shared taxi and on our way inland on an immaculate, new highway. It turns out that Sierra Leone has very good roads throughout the country, a welcome reprieve following our Liberian adventures! After a few hours we bid farewell to our taxi at a village called Potoru and managed to find a basic $5/night guest-house for the night.

The next day we jumped onto two motorbike taxis and headed down a good dirt road towards Tiwai island, a wildlife sanctuary in the middle of the Moa river. This sanctuary was founded in 1987 by a British scientist who recognised that protecting this incredibly bio-diverse, uninhabited island would ensure the survival of many rare species while at the same time generating tourism income for the surrounding communities.

|

| Magnificent forest trees on Tiwai Island |

|

| Forest fungi |

We spent three nights alone on the Island and did a number of guided walks where we saw lots of red and white colobus monkeys climbing enormous trees while underfoot countless armies of termites devoured any dead trees or branches - and your toes if you stood still for too long. Every few minutes we’d hear an eerie, loud wooshing sound as giant Yellow Casqued hornbills flew like jungle helicopters overhead. The island has chimpanzees and pygmy hippopotami but we were not lucky enough to spot any. Occasionally, we’d pass an old pit in the forest which turned out to be illegal diamond mines dug by rebels during the civil war twenty years before. It seems that if you pick the right spot in Salone you can just dig down a few meters in loose alluvial sand and find diamonds! Interestingly, anyone can get a small-scale miner’s license to mine diamonds provided you pay the government a fee of about US$100/year.

|

| Abandoned rebel diamond mine |

After a serene few days on the island we returned to the mainland for a three day guided hike that forms part of the Tiwai Heritage Trail, which visits the traditional forest villages that surround the island. This trail was created to ensure that these remote communities benefitted from protecting the indigenous forests. This trail was really interesting, giving us insights into the beautiful forests that cover this region while at the same time getting to meet the people and learn about their culture.

|

| We spent days admiring the incredible Tiwai forest canopy |

Sierra Leone, unlike Liberia, is about 80% Muslim and on arrival in each village we would be met by a welcoming party of village elders, traditional leaders as well as the local imam. We would then spend an hour or so in the barri, a covered meeting area supported by poles or mud-brick columns, where a number of welcome speeches would be made. In Sierra Leone, Chiefs and Paramount Chiefs are elected positions and are not hereditary. While walking through the villages, it was common to see election posters for the different candidates standing for chieftaincy positions. This was the first time we’d ever seen traditional leadership in Africa that was not based on an hereditary system.

|

| Meeting the imam and traditional leaders at a village on the Tiwai Heritage Trail |

Interestingly, in this part of the world it’s pretty normal for women to go topless. We found ourselves blinking a few times while sitting and talking to a local imam in the barri who was wearing just a pair of shorts and sitting alongside a group of topless women who were chatting amongst themselves. Ancient animist beliefs have been merged with Islamic ones and inter-marriage between Muslims and Christians is common. Generally the whole attitude to religion is pretty relaxed, peaceful and tolerant - a fact that they mention often with pride. The Taliban should be sent to Sierra Leone to learn to chill out a bit!

|

| Village on the Tiwai Heritage Trail |

Islam in West Africa came by the way of the indigenous North African Berber people who had adopted the religion around the 10th century. Berber merchants, with their camel caravans, were instrumental in connecting the gold rich regions of West Africa to the growing trade routes that were criss-crossing from the Far East to the Western-most parts of Europe. Gold coinage was needed to facilitate the flow of Chinese silks, Indian spices, Venetian glass, English wool and the many other tradeable “goods” of the time including enslaved people, cotton, ivory, fruits, vegetables and salt. This region was deeply involved in slavery and the slave trade in the past and an interesting fact we were told was that it was often relatively nearby communities from within the same Mende ethnic group who would attack a neighbouring village and enslave the vanquished villagers. It is supposedly still sometimes possible today to see which families are descended from enslaved peoples, based on the amount of land they own. The Berbers had held onto large chunks of their pre-Islamic, animist beliefs and, through their peripatetic trade, spread a far less orthodox version of the religion into West Africa than was practised by their Arab neighbours.

|

| Crossing a bridge |

In each village that we passed through, we were given a “heritage site” tour. Initially we expected that this might feel a bit contrived and overly ‘touristy’ for our tastes but in the end we found that each site was quite different and interesting in its own way. These sites gave us a taste of the deep integration of animist beliefs with modern day Islam and everyone participated in the rituals, including the imams. One site was a massive, sacred Cotton Tree where various rituals are performed for human fertility and good harvests. Other sites were sacred caves where people performed similar rituals and which proved a safe hiding place during the war. The last sites were ancient graves where, supposedly, giant ancestors were buried. These giants had stones marking their feet and their heads and thus looked to have been three metres tall... There were many stories of how these giant warriors had defended their villages during invasions by neighbouring communities and this defensive baton was passed down to the modern day defenders of these communities: the Kamajor militias. These militias were made up of motley crews of village people who defended against the invasions by RUF rebel forces and Sierra Leonean government “sobels” (soldiers by day, rebels by night). The Kamajors were certainly a colourful crew - they were made up of mostly forest hunters who knew the terrain better than anyone. They wore elaborate outfits adorned with various mutis and talismans in order to provide protection against bullets. Interestingly, the local villagers smiled happily when they heard we were South African.

|

| Kamajor fighters (from Sierra Leone civil war) - not my photo. Source |

During the early years of the civil war, a South African mercenary outfit called “Executive Outcomes” was recruited by the short-lived democratic government to fight the nightmarish rebel group, the Revolutionary United Front who infamously amputated tens of thousands of people’s hands and feet to spread terror through the villages. Executive Outcomes rapidly defeated the rebels in a few months but international condemnation of the government’s use of mercenaries forced Sierra Leone to cancel their contract and Executive Outcomes left the country. Within months the RUF rebels had recaptured much of the territory they had lost culminating in the brutal attack on Freetown known as “Operation No Living Thing”. While ethically and instinctively we are against mercenaries of any kind, it was sobering to think how well-intentioned, intellectual decisions in faraway, comfortable board rooms ultimately allowed terrible violence to be committed against defenceless people. If the voices of the rural Sierra Leoneans most affected by these decisions had been heard, might they have made differently?

**** SIERRA LEONE HISTORY *****

We didn’t have the time to do a historical summary as we did in previous blog posts. Here’s a link that gives a concise version of the fascinating history of Sierra Leone AKA “the Lion Mountain”. While there are similarities with neighbouring Liberia, there are huge differences too:

History World: history of Sierra Leone

**** END OF SIERRA LEONE HISTORY *****

Sierra Leone is unusual in West Africa for being overwhelmingly dominated by just two ethnic communities: the Mende and the Temne (pronounced “Timnee”). Our very knowledgeable guide, Mohammed, was a fountain of knowledge about the history and culture of the area (we highly recommend Mohammed as a guide, his Whatsapp: +232 79 795174 ). The local cultures are deeply intertwined with the indigenous forests that cover this entire region. Each family has their own piece of forest which they use for building materials and firewood. These forests contain some giant hardwood trees which people treat as savings to be used for emergencies or an important event. If such an event was to occur, the family will meet to discuss the issue and might decide that one giant tree should be harvested and they’ll then sell it to a timber merchant either as unworked logs or sometimes they’ll first saw the logs into planks. We queried whether desperate or greedy families wouldn’t potentially cut down the whole forest for short term profit, but Mohammed explained that the majority of the biggest tree species are worthless for timber purposes so these wouldn’t ever be cut down.

In one village we found a blacksmith hard at work using a furnace based on a design that has been in operation in the region for over a thousand years. With the bellows pumping and his hammer pounding, he was busy producing machetes from the leaf springs of old trucks.

|

| Pounding the steel truck spring into a machete |

|

| Pumping the blacksmith's bellows |

|

| A village chair maker |

The agriculture in this area involves the slash and burn method of clearing forest and then burning the under-brush. As far as we could tell, the areas being cleared had been farmed years before as the trees weren’t yet particularly large. These cleared plots were mostly used for farming rice, cassava and a few vegetables. Some plots had been converted to oil-palm plantations of between 50 and 100 trees. Oil palm plantations have caused the decimation of indigenous forests in South-East Asia so we asked whether this was a risk in this area. We were told that managing even just 50 oil palm trees was enormously labour-intensive so it wasn’t a very attractive way to use family land. For the sake of these magnificent forests, one hopes that mechanised oil-palm farming doesn’t reach this part of the world.

Farming in a forested region is tough as monkeys and other animals constantly raid your crops. The farmers have devised various ingenious traps to catch (and eat) these animals which is sad to see but we couldn’t see a workable alternative plan.

|

| Harvested food is stored in the roof. The cone shaped objects on the vertical pole prevent rats climbing up and eating the harvest. |

|

| One of the giant, sacred Cotton Trees on the Tiwai Heritage trail |

On each morning of the village tour trip, we would wake to the sound that has serenaded us throughout Central and Western Africa: the soft brushing of a grass hand broom on the ground. It is quite amazing how people will wake up at the crack of dawn every morning and sweep the ground around their huts. What’s even more amazing is that this very early morning chore is not to remove litter or any kind of mess - there is little rubbish lying around - it is just for the aesthetics of a brushed sandy area. On the coast people sweep the beach sand, in the forests they sweep the red earth. We grew to love the gentle swoosh, swoosh sounds every morning and appreciate the fastidiousness of the culture.

|

| A homestead's palm oil orchard |

|

| A monkey trap: the monkey walks along the branch and through the gap. The the noose is yanked upwards by a flexible branch and snares the monkey. |

A trap for catching wild animals on the ground

One of the villages we visited was very poor and it seemed most of the kids were under-weight and tiny for their age. Few of them were attending school. Most of the other villages did have a basic primary school with a standard design of three classrooms with glassless windows where two grades shared a room. Government teachers in Sierra Leone - and the region in general - earn about US$100 (R1500) per month. Teachers employed directly by the community or local NGOs earn as little as US$30 per month. Recently, the government supposedly introduced free primary school education, but everyone we met scoffed at this saying that while officially school fees were not required, the schools were demanding so many other new fees that there was little reduction in the cost to parents.

|

| Village mosque |

|

| Another village bridge |

|

| On the path to the next village |

Healthcare in the country is a huge challenge. Everyone, except pregnant mothers, has to pay to be treated at the government hospitals. A broken leg can typically cost US$250/R3500 to treat which often forces families into debt. If you don’t pay, you don’t get treated. While the current president, Maada Bio, has made the introduction of “free education” a central focus, most of the people we spoke with said that the previous president, Ernest Koroma, was much better and credited him for building Sierra Leone’s impressive road system (with significant help from the Chinese government). Liberia needs to copy and paste Sierra Leone’s road building plan.

|

| We like the Sierra Leonean mud hut design - especially the verandah which is particularly necessary during the rainy season. |

After a very interesting week in a beautiful area, we jumped on motorbikes which took us to the main highway and then caught a shared taxi to the city of Bo and then a minibus to Freetown. The entire road was tarmac and in excellent condition. On our arrival on the outskirts of Freetown there was some confusing hopping in and out of vehicles in places with names we would soon come to know well: Willbeforce (pronounce “Bafors”), Jui and Waterloo. By early evening we had found our lodge: the first place with a cool backpacker vibe since we’d left Ghana almost two months before.

When arriving in a new country there are a few things we always do. First, get a cellphone SIM card and load data so you can use google maps to find an ATM that will take a foreign bank card. A surprisingly difficult challenge in Freetown was getting cash from an ATM. The local currency is called “leones” and the biggest note is 10,000 leones which equates to US$1. Most ATMs have a maximum limit on the number of notes they can dispense at one time - generally a stack of 40 notes is the maximum that can pass through the cash dispensing hole. So in Sierra Leone you can only withdraw the equivalent of US$40 per transaction and then the bank back home in South Africa deducts a hefty minimum international cash withdrawal fee which amounts to about 15% of your withdrawal amount. This proved quite an expensive headache which forced us to use some of the US dollars cash we were carrying. In the end our problem was solved by a combination of locating a bank that would allow us to swipe our credit card inside the bank and then withdraw more than the US$40 maximum or, alternatively, to use the World Remit phone app to send money to one of the many cash transfer agencies that can be found on almost every street corner in West Africa. The end result was that at any one time, we would be carrying big wads of cash containing millions of leones. In the past, Sierra Leoneans were permitted to use US dollars cash for all transactions which was especially helpful when buying a car or a house. But recently the government banned this practice, forcing people to carry big bags of cash leones whenever they made a big purchase. Sierra Leone feels like a well-run country where most things seem to work quite efficiently, except for the monetary system. The country desperately needs some bigger notes: all other countries have notes representing $10 or more in value - a $1 note is just too small. Once we’d left Salone, we saw a newspaper article announcing that the government will be redoing the currency in October 2021, certainly a much needed intervention.

|

| Wet and loaded! |

|

| Sucking a bissap icey in a bustling market in downtown Freetown |

With our first local cash in hand, we would then visit the shops of the new country we find ourselves in, to recalibrate our brains to local prices. Typically, we would do this recalibration using a few standard items like a tin of evaporated milk (crucial for coffee drinkers as no fresh or even UHT milk is easily available), a plate of street-food and a packet of drinking water. The latter is by far the most common way to consume drinking water in Ghana, Liberia and Sierra Leone. If you’re thirsty, you just need to look for a cooler box on the sidewalk or listen out for the call of “Ko Waaataaa!” (“cold water”) and then you grab a 500ml clear plastic bag of water, bite off the corner and suck it dry in one go. This does result in a lot of empty plastic water bags littering the landscape but one would imagine that these bags would degrade a lot faster than the hard plastic bottles used elsewhere in the world. It was noticeable how much cleaner Sierra Leone was than Ghana and Liberia. We’re not sure exactly how they achieve this, but there is a lot less litter than one might expect in a bustling city. On completing our “price calibration” for Salone it was clear that it was quite a bit cheaper than Liberia and Ghana for most things.

|

| The green rolling hills of beautiful Freetown |

Freetown, Freetown… what a cool, beautiful city! Straddled over a series of green forested hills with glorious views of the ocean, this city really grew on us. So much so that we’d have to say that, as African cities go, it ranks second only to Cape Town in beauty and is certainly one of our favourites. The public transport is super cheap and easy: just shout out the word “bike” and you’ll have multiple motorbikes instantly at your side and ready to take you short distances for $0.20/R3. For longer journeys, or when it’s raining, just look for a keke (3-wheeler tuktuk) which might charge you $1 to travel about 8km. Longer journeys might involve a shared taxi for $0.50 or a minibus for a bit less.

Hilly cities are always a bit confusing as the roads can’t form a symmetrical grid but, after a while, we began to work out Freetown’s idiosyncrasies. You had to learn which roundabouts were transport hubs and which places needed a bike and which needed a keke. The only thing we never understood was the kekes’ mysterious pricing system: even locals were at a loss as to why a short journey in one direction would cost three times more than a longer journey in another direction. But with prices so low, we couldn’t complain. The centre of Freetown has a gigantic Cotton Tree which is at least 250 years old and is where the freed enslaved people from Nova Scotia stopped to pray on their arrival in Freetown. To this day, it is considered a sacred place at which spiritual ceremonies are performed. In its branches sit dozens of hooded vultures which are to West Africa, what crows and dogs are to Southern Africa: the urban scavengers.

On entering Sierra Leone, we’d found out that there were abundant supplies of Covid19 vaccines in the country which the public didn’t seem particularly interested in. We headed off to a local government hospital and sure enough we were the only people there to be vaccinated. After a very quick process, we had our Sinopharm jab and were on our way. At that point (July 2021), less than 1% of Sierra Leoneans had been vaccinated, and there still seems to be very little interest in getting jabbed.

|

| Vaccinated! Thanks Sierra Leone (and China) |

While Sierra Leone has about double the population size of Liberia, it is very similar in terms of climate and day to day life. Covid prevention practices border on a theatre of the absurd. Covid restrictions applied to public transport include motorbike taxis only being allowed one passenger (normally up to three passenger), while kekes are allowed only two passengers (normally four passengers). On the other hand, minibuses (called “poda podas”) - which have much, much worse ventilation than a motorbike or a keke - are allowed to operate at 100% capacity. Not only that, virtually no-one in these buses wears a mask, except for the approximately three minute period when they reach a police checkpoint and where everyone has to put on a mask, disembark, wash their hands, walk to the other side of the checkpoint rope, and get back into the same poda poda again. As soon as the bus departs the checkpoint, everyone (except us) takes off their mask. Very few people wear masks on the streets and even in banks and government buildings, masks were the exception rather than the norm, even for bank/government employees. It is known that the highly contagious Delta variant is circulating in Sierra Leone and yet the statistics show just 120 Covid deaths in the past 18 months.. At the peak of their “Delta wave”, they experienced an average of just 50-100 infections and two deaths per day. We asked doctors working at the main hospital whether they had observed any panic for oxygen like that seen in neighbouring Liberia and they said no. Why the experience in Liberia and Sierra Leone should be so different is a real mystery, and again all we can do is appeal to the big funders of medical research to devote some dollars to better understanding what is happening with Covid on our continent (interesting studies here https://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12879-021-06701-8 and here https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8107224/ on a possible inverse link between malaria and Covid19). As things stand, it is hard to see how Sierra Leone will convince even 10% of their population to get vaccinated. As a Sierra Leonean told us: “when we had Ebola, we could see that it was dangerous, we saw the vehicles carrying away the bodies, but with Covid we don’t know anyone who’s got very sick or died...”

As one drives around the outskirts of Freetown, it is remarkable just how many giant houses are in the process of being constructed. These houses, often three stories high, are bigger than any houses we’ve seen anywhere in the world (with the exception of Tibetan houses). When we asked how come Sierra Leoneans had so much money to build these houses, people just chuckled and talked vaguely about “businessmen” but we never got a satisfactory answer as to why there is such a construction boom going on in the country. Freetown houses also stood out as being in exceptional condition. In most tropical African cities, cement buildings are soon covered in green moss and black mould and can look quite weathered. In contrast, in Sierra Leone the buildings all look freshly painted with bright colours. We were told that people typically paint their homes once a year, and the local paint seemed to be very durable.

The guesthouse we were staying in was in a nice part of town with many large, luxurious houses. However, next door to the guesthouse and scattered throughout the suburb we saw open plots with a few corrugated iron shacks housing families. It turns out that the country’s land registry system is quite corrupt and even when you have bought a plot and have all the necessary documents to prove it, it might happen that someone else could just start building their own fancy house on your land. In some cases, these usurpers of land ownership have bribed the land registry officials to transfer the plot into their name. If you dispute this transfer of ownership, you could end up tangled in a long complicated legal fight without any guarantee of success. You might even be forced to sell your plot to the house builder as they will complain that they have already spent a huge amount of money building their house. So to avoid all this hassle, if you legally buy a plot but are not ready to begin building immediately, you find a homeless family and allow them to put temporary shacks on your land for free in order to prevent someone illegally building permanent structures on your land. Then, when the land owner is ready to build, there is apparently no difficulty in requesting the shack dwellers to vacate the land. It seems that land and construction is the main way that people “save” money as the financial system is not trusted. If you have some savings, you either have to take the risk of having US dollars cash hidden under your bed or you buy some land and begin building a house. Even if building that house takes years, it’s still regarded as the best way to save for the future.

|

| All over Freetown there are buildings like these under construction |

After a few days in central Freetown, we headed about an hour down the lovely Freetown peninsula to Bureh Beach. The Freetown peninsula has many kilometres of beautiful beaches located beneath forested hills. We found a lovely spot on Bureh Beach to spend about ten days doing some more “digital nomading” work. Sierra Leone’s historical links to Jamaica meant that Rastafarians were common and cannabis was easily found. The dominance of Islam also meant that drunkenness was rare. This normally lively tourist area was totally dead, thanks to Covid19 and the start of the rainy season.

You do not know rain until you’ve experienced Sierra Leone’s rainy season!

This country has 3000mm (3 metres!) of rain per year which is by far the highest rainfall on the continent. All this rain falls during the five month long, summer rainy season. Think about the most intense cloudburst of rain you’ve ever experienced and then imagine that falling for 10 hours every day. At some point, normally in August, the legendary seven-days-rain begins when it rains torrentially, non-stop, day and night for a whole week. The country gets so much rain that few people bother to put up gutters for rainwater collection; you just need to place huge buckets under any part of the roof edge and they fill up daily and in no time. The rain was so heavy during our stay in Bureh that the shop mamas added “how di rain?” to the usual greetings of “how di bodi, how di day?”. The answer that got the most appreciative response was to sigh and say: “di rain is di rain”. The drainage system in Freetown required to avoid flooding is quite impressive: deep gutters and well-built drains channel the floods neatly down the steep hills. These drains do, unfortunately, gather what litter there is and deposit it all on the inner city beaches. Lots of rain also meant LOTS of mosquitoes. Freetown’s mosquitoes are next level: they’re not particularly big but they are by far the craftiest of all the many mosquitoes we’ve met in the tropics. If you are not 100% perfect when tucking in the mosquito net into your bedding, then these little buggers could find the smallest crack to enter your sanctum and share their itchy love.

|

| Bureh beach on the Freetown peninsula, Sierra Leone |

We were mostly self-catering on our camping stove during these days at Bureh which meant regular visits to the markets. The vegetable selection was somewhat better than in Liberia but still a bit bare - one had to know a special little shop behind the main market where you could get carrots and lettuce. Each country we visit has its little sweet surprises. In Salone we were amazed to see youngsters pushing ice-cream wagons from which emerged delicious, cheap ice-creams: proper Conetto ice creams for $50c! It’s a total mystery how this was happening in a region that struggles to produce fresh milk. The other treats were FreeGells sweets, which are very similar to Halls sweets in South Africa but much much cheaper at just $20c per pack. Kids would wander about with buckets of delicious homemade peanut brittle, sesame seed crunchies and butterscotch jawbreaker sweets too. Bananas were super cheap but Mangos and Avos were much more expensive than elsewhere in the region.

|

| Delicious sesame cakes and peanut brittles |

|

| Young entrepreneurs |

|

| Chilling out at Bureh beach, Freetown peninsula, Sierra Leone |

The shops in Sierra Leone are almost all tiny wooden or metal cubicles that sell a wide range of things spaza-style. There are a handful of super-markets in Freetown but almost everyone relies on tiny micro-shops for their daily needs. The biggest shops in outlying towns would have just a counter where you’d be served by the shopkeeper from a few shelves on the wall behind him. From what we can see, West Africa has two distinct approaches to retailing: in Ghana/Gambia almost all retail happens through supermarkets and large stores with little side-walk trading. There might be a little fresh produce market here and there but in general you have to enter a big shop to buy stuff. The Liberian/Sierra Leonean model of retailing is dominated by tiny shops – mostly erected on the side-walk. In addition there are loads of people wandering about with wheelbarrows or basins on their head filled with a wide range of products. It would be fascinating to study which approach is more beneficial to the economy. One would expect that larger shops would be able to sell more cheaply thanks to economies of scale, but then they have much larger overhead costs like air-conditioning, security, rent and staff. The microshops have none of these expenses and we found their prices very competitive. Hundreds of microshops instead of one large supermarket would seem to spread wealth and employment more widely in society.

|

| Bureh beach |

|

| Bureh beach has lots of cool lodges and restaurants on the beach |

After Bureh Beach we headed further down the peninsula and then jumped onto a boat to Banana Island. Here we found a lodge called Dalton’s Guest House founded and run by an eccentric guy called Greg. The island has a village of about 500 people and is dominated by a beautiful forest. The lodge itself was built into the forest with the giant communal restaurant and chillout area partially supported by living forest trees. We enjoyed some nice walks in the forest and through the beautiful village filled with pretty flower gardens and some monstrous Cotton Trees. We also did a boat trip to the far side of the island to go snorkelling - our first “touristy” activity in many months - it felt quite nice! The rains were still going strong so we felt constantly damp - our backpacks even started growing mould. We met a few cool travellers and got to observe youthful Instagram travel culture first hand.

|

| Our travel buddy on Banana Island - clearly our own photo skills are lacking! |

Nzinga's instagram and Ellie's instagram.

|

| Banana Island, Sierra Leone |

|

| Banana Island, Sierra Leone |

After a week on Banana Island we decided to return to the drier life in Freetown. During the previous few weeks we had become masters at travelling from Bureh to Freetown which involved four changes in public transport, each with its own peculiarities. The reason for these frequent trips to town was due to us having to visit the Guinean embassy in order to get a visa to visit this, the next country on our route. While the embassy staff were friendly, the visa application process was bizarre. It seemed that one first needed a letter of approval from a security office inside Guinea and so the embassy had to send copies of our passports to Conakry (the Guinean capital) to secure this letter. We were told to return in a few weeks when we were sure to get our visa. In the end this proved a total waste of time as every time we returned we were told to come back in a few days or weeks to no avail. It was not clear whether this strange procedure was Covid-related or whether there were other security concerns. Sierra Leoneans are able to cross in and out of Guinea without any visas or problems so it didn’t seem to be a Covid restriction. The fact that a month later there was a coup d’etat in Guinea with the elderly president overthrown by young soldiers might indicate that the government may have just been generally suspicious of anyone coming into the country.

After a few more days in lovely Freetown we headed north to two towns in the interior. We first stayed in a guesthouse inside an inspirational school for the deaf in the town of Makeni. The town itself wasn’t anything special but it did have a heaving, vibrant market which was fun to walk around. One restaurant we visited advertised that a portion of the proceeds of each meal went to supporting the ‘strit pickin’ - pidgin for street child. As South Africans, the reference to children as “pickins” or “pickinins” is rather offensive so we had to keep reminding ourselves that the word has no such negative connotations in Salone.

|

| Makeni's bustling market |

We then headed further north to Kabala, which sits at the foot of a pretty mountain. There we wandered about the countryside villages where farmers were hard at work preparing their fields for rice planting. In both the towns and the villages in Sierra Leone it was remarkable to see how big the average home is. Almost every house has a large verandah - a good spot to hang out during the torrential rains. The houses are very well built; the local builders seemed to be a lot better at constructing using concrete and reinforced steel than we tend to see in the rural areas of the Eastern Cape. Being able to build homes that last generations is crucial to ensuring that there is an inter-generational transfer of wealth from parents to children that can, over time, lead to sustainable improvements in standards of living. One of the challenges we’ve seen back home is that substandard construction leads to houses often only lasting a few decades which means that each generation has to continually use up their meagre savings to rebuild their family homes, trapping families in a cycle of poverty that is hard to escape.

|

| Overlooking the pretty town of Kabala |

|

| View from our guesthouse in Kabala |

After a couple of days in Kabala we returned to Freetown in a minibus that had a live cow on the roof! The journey once-again involved countless checkpoints with our fellow passengers performing the ridiculous ‘mask on, disembark from the vehicle, wash hands, mask off’ Covid theatre each time. The next day we got our second dose of the vaccine in the hospital where, once again, there was nary a soul getting vaccinated and where even the visibly bored nurses weren’t wearing masks. Armed with our blue Sierra Leonean vaccination cards we were thrilled to join the world of the fully vaccinated.

|

| "I need to go to Freetown with my cow" |

Getting a cow off the roof of the Podapoda minibus

We spent our last few days in Freetown enjoying the vibe of this lovely city. We hiked up the highest hill and enjoyed magnificent views over the city as well as views of the site of a catastrophic land-slide in 2017 where more than a thousand people died when a steep hill on which they’d constructed their homes was destabilised by heavy rains. On the way up the hill we found a lot of rock-breakers working next to the road. We’d seen people doing this work elsewhere but this was the first place we got to talk to them and understand how their business worked. These men and women (and a few kids) lived on properties alongside the road where giant granite boulders were plentiful. Using a combination of sledgehammers and fire, they would break off big pieces of this rock which they’d pile next to the road. Then began the very boring work of hitting these rocks with a hammer and slowly breaking them down into much smaller stones that can be used to mix concrete. These stones are sold by the bucket load to construction companies and people could earn about $10 to $15 per day depending on how long they worked.

|

| Breaking rocks in Freetown |

|

| Smashing rocks into building stones, Freetown |

We also visited one of the city’s most popular beaches - Lumley - which has lots of beachfront cafes and bars. Sadly the beach is covered in plastic pollution washed out of the city drains and into the sea. Hopefully the beaches will be cleaned when tourism restarts in earnest.

|

| Throughout our trip, in every country, these colourful Agama lizards have been everywhere. |

Red-headed agama lizards fighting

On one of our final touristy jaunts about the city, we visited the Peace Museum which is part of the Special Court for Sierra Leone complex where war crimes from the civil war were prosecuted. The Peace Museum was quite harrowing with horrific images of the brutality of the war. Towards the end of our visit, a museum official came over to chat with us and shared his personal story of being captured and tortured by rebels and by the junta running the country at the time.

We also visited the National Museum which has a fascinating collection of masks and outfits worn by the different secret societies that are an integral part of Sierra Leonean culture. The vast majority of adults in the country are members of ancient secret societies that they join on achieving adulthood. Men mostly join the Poro society when they are teenagers and the initiation rituals and lessons learnt there are highly secret. Similarly, women join the Bundu/Sande society which traditionally includes female circumcision as part of the initiation ritual. While there has been some efforts by mostly urban women to alter the Sande society initiation rituals away from circumcision, it is still the case that about 90% of Sierra Leonean women have experienced female genital mutilation (FGM). One of the tricky issues to resolve is the replacement of income for the women hired to perform the cutting, for whom this is their only profession. West Africa, Guinea, Mali and the Gambia all have rates of FGM of over 75%. In the east, the worst culprits of the barbaric practice are Ethiopia, Egypt, Sudan and Somalia. Victims of FGM experience not only the pain of the cutting but terrible complications during and after childbirth. And this in regions where access to medical care is of the poorest in the world.

|

| Female Genital Mutilation in Africa |

The various secret societies and ethnic groups in the country have elaborate ceremonial outfits and incredible masks that are worn by the fetish priests (known locally as “devils”) who lead the community in ceremonial masquerade dances. Different outfits and masks indicate who is permitted to join a dance ceremony - in some cases anyone from any group can join, while other outfits indicate that only members of that particular society may participate.

|

| Elaborate ceremonial costume, Sierra Leone |

|

| Ceremonial masks, Sierra Leone |

We didn’t get to see any of these ceremonies ourselves, but here’s a cool video showing a masquerade ceremony.

And here’s another great dancer who’s part of a similar ceremony although in nearby Cote D’Ivoire, not Sierra Leone, but we’re putting him here just because he’s so impressive.

Incredible Zaouli dancer, Cote D'Ivoire

After an easy five weeks in Sierra Leone, we gave up on ever getting visas for Guinea. So we jumped on a ferry that took us to the airport across the bay and did a short plane hop over Guinea to visit Africa’s smallest country: The Gambia.

As our aeroplane lifted off, we took one last look at lovely Freetown and the land of the Lion Mountain and thought: “We go si back!” (See you later!)